Superbugs and Hospital-Acquired-Infections.

By Trisha Torrey, verywell health.

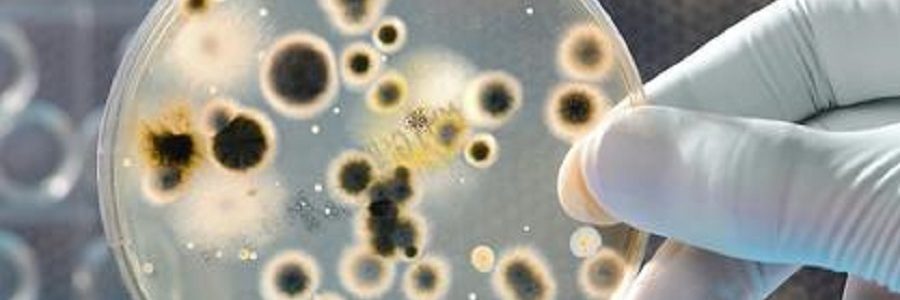

No discussion of patient safety would be complete without covering the growth of superbugs, infectious organisms that make patients sick and may even cause death. They are called superbugs because it’s very difficult to kill them with existing drugs, which limits treatment options.

Superbugs are known by names such as:

- Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA)

- Clostridium difficile (C.Diff)

- Vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE)

- Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) and Carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae (CRKP)

- Necrotizing fasciitis, the flesh-eating bacterial disease

Natural, but Life Threatening

Perhaps surprisingly, some of these organisms are present naturally in our environment and they do not make healthy people sick. For example, about one-third of people are “colonized” with the bacteria Staph aureus, meaning it lives on the skin in the noses of people without causing disease. Approximately one percent of people are colonized with the antibiotic-resistant form of staph aureus (known as MRSA). The percentage is higher for people who have been recently hospitalized.

C. Diff lives all around us, too, including in human digestive systems. The problem with this superbug is that it won’t cause problems until the person begins to take antibiotics for another illness. At that point, the C. Diff can colonize out of control making the infected person much sicker.

Superbugs are invisible and can survive on surfaces for up to three days. That means that they can be transferred when one infected person simply touches another person. They can also be transmitted when the patient touches something on which the pathogen resides, such as a stethoscope, a TV remote, a computer mouse, or shared athletic equipment.

HAIs: Hospital-Acquired (Nosocomial) Infections

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), an estimated one in 25 Americans contracts a hospital-acquired nosocomial infection (HAI) each day. They are admitted to the hospital injured, debilitated, or sick and are easily susceptible to a colonized infection. Others in the hospital—some sick and others healthy—can introduce the pathogen and the superbug can then take hold and begin growing out of control.

Infectious pathogens find easy access to the bloodstream of a patient with an open wound from an injury or surgery. Once the germs enter the bloodstream, the patient is said to have sepsis or septicemia. Patients who are sick with another disease or condition may have a compromised immune system, making them too weak to fight off a superbug. The elderly are especially susceptible because their systems may already be fragile due to their age.

Once the patient is infected, the hospital stay is extended, sometimes for months. In some cases, the infection can be controlled enough so the patient can eventually leave the hospital. But many patients aren’t so lucky. Of the 1.7 million Americans who are infected in hospitals each year, at least 99,000 of them die from those infections.

Due to the prevalence of HAIs and the fact that many are preventable, the Medicare system penalizes hospitals with high rates of HAIs. In these instances, Medicare reimbursements are reduced and the penalties are seen as a way to forcefully encourage hospitals to step up prevention efforts.

How Can You Avoid Infection?

There are a number of additional steps that patients can take when they are serious about preventing hospital-acquired infections. For instance, you can look into the infection rate of a hospital or doctor and be aware of how infections are most often spread in hospitals. Basic sanitary practices can help tremendously in reducing infections as well.

Superbugs and hospital-acquired infections can be a scary topic that you might not want to think about. However, it’s important to remain aware of the potential risks so a seemingly minor hospital stay doesn’t turn into a larger problem. A little diligence and knowledge before your hospital admission can make a difference.

From Consumer Reports.

When you enter a hospital, the last thing you want is to end up sicker than you started. But that happens all too frequently in U.S. hospitals, often because of preventable problems. A leading cause: urinary catheters. More than 30 percent of hospital-acquired infections involve those devices, making catheter associated urinary tract infections, or CAUTIs, one of the most common kinds of hospital-acquired infections, according to the national Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Some research suggests the infections contribute to thousands of deaths a year.

Now, for the first time, our hospital Ratings include information on how well hospitals in your community and across the country compare in preventing the infections, and on how they stack up on other measures of hospital performance.

Related Topics

Cascading problems

A urinary catheter is a tube that’s threaded through your urethra into your bladder, allowing urine to drain into a bag. That helps measure urine output, and the device is essential for patients who can’t get out of bed or use a bedpan.

But infections can occur when bacteria travel along the outside or inside of the catheter into the bladder or kidney, or when urine flows back into the tube, contaminating it. And sometimes catheters are left in longer than necessary, or used mainly for the convenience of the hospital staff. That’s worrisome, since the longer the catheters are in, the greater the potential for infection. For each day a patient has a catheter, the risk of infection increases by five percent, researchers estimate.

And while urinary tract infections might not sound serious, they can be. “They’re often the first thing that goes wrong when you’re in the hospital, which can trigger a cascade of other problems,” said Lisa McGiffert, who heads Consumer Reports Safe Patient Project, which aims to stop preventable medical errors, including hospital infections.

For example, urinary tract infections sometimes spread to the bloodstream, which can lead to deadly complications. More often, the infections are treated with antibiotics—which in turn puts patients at increased risk of adverse drug reactions, development of antibiotic resistant infections, or a dangerous intestinal infection caused by a bacterium called Clostridium difficile, said Sarah S. Lewis, M.D., an epidemiologist with the Duke Infection Control Outreach Network at Duke University. That infection, called c. dif., is now rampant in U.S. hospitals. All told, research suggests that urinary tract infections in hospitals contribute to more than 13,000 deaths a year.

For all those reasons, “There is a high priority now on CAUTI prevention,” Carolyn Gould, M.D., who leads the acute care team in the division of healthcare quality promotion at the CDC, said.

For example, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services no longer pays most hospitals for the treatment of certain hospital-acquired infections, including urinary tract infections, figuring if the problem happened in the hospital, the hospital should be financially responsible.

In addition, hospitals must now report some infection rates to the government, with the hope that the information will help hospitals track the problems and take steps to improve. In addition, the data is made publicly available, which is why we can now include it in our hospital Ratings.

What we found

Our analysis of that information provides a snapshot of how hospitals all across the country compare in preventing the infections. We looked at infection rates in ICUs from April 2012 through March 2013 in about 2,300 hospitals in all 50 states plus Washington, D.C., and Puerto Rico.

The good news: Some hospitals have been able to eliminate the infections from their intensive care units. More than 400 hospitals (or 18 percent) reported zero infections, which earns them our top Rating.

The bad news: More than 300 hospitals earned our lowest Rating, indicating they had at least twice the national average number of those infections.

Why are so many doing so poor? Researchers from Columbia University and the CDC suggest it may be in part because hospitals have not yet focused on CAUTIs to the same extent that they have other kinds of infections. For example, while up to 97 percent of adult hospital intensive care units have put in place a policy to reduce central-line-associated bloodstream infections, no more than 68 percent had taken similar steps to prevent CAUTIs in those units. And among hospitals that had instituted policies, only up to a quarter were following them. In contrast, up to nearly three quarters of hospitals followed protocols to prevent central-line infections.

Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital

At the Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital Rahway in New Jersey, preventing urinary tract infections is a priority—and efforts have paid off. The hospital reported no infections during this period and thus received our highest Rating.

What does it do? Hospital staff discusses each patient’s need for a catheter once a day, during morning rounds. Twice a day, ICU nurses complete a checklist for each patient to assess the appropriateness of the catheter. “If the patient doesn’t meet the appropriate indication for each item on the list, the catheter is removed,” Debra Toth, R.N., nurse manager of the critical care unit, said. But rather than wait for a doctor to make the call or write the order, which could take time, “all nurses are empowered to remove the catheter,” based on a set of evidence-based guidelines, says Angela DeCillis, R.N., nurse manager of one of the telemetry floors at the hospital.

What you can do

If you or someone you care for is in the hospital, take these steps to reduce the risk of developing a urinary tract infection from a catheter.

Make sure you really need one. Chances are there is a good reason for starting a catheter, but sometimes they might be put in mainly for the hospital’s convenience. If you feel you can go to the bathroom on your own or use a bedpan, say so.

Ask every day if you still need the catheter. If the answer is yes, ask why. If the answer is no, ask to have the catheter removed.

Make sure everyone washes his or her hands. That means cleansing hands thoroughly with soap and water or an alcohol-based hand rub before and after touching the catheter. The area where the catheter is inserted should be sterilized, too.

Check for a leg strap. That helps secure the catheter and keeps it lower than the bladder. Nurses should regularly check how the catheter is positioned and maintained.

Make sure the bag is emptied regularly. And that the catheter is cleaned.

Watch for fever. That’s usually the first sign of a urinary tract infection. If you suspect a problem, speak up. “It is really important to be persistent if there is a problem,” McGiffert said. “CAUTI is a preventable infection that can get out of hand quickly if you don’t get it taken care of.”

Aug. 2016.

Editor: Although the publication date of this article may not be current the information is still valid.

> See Patient Safety Toolkit

_______________________________________________________________________

Common Hospital Infections and How They Spread

By Christina Holt from Pregnancy and Baby.

The World Health Organization reports that the most common infections that patients get from hospitals include infections of surgical wounds (like those of a cesarean), urinary tract infections and lower respiratory tract infections. But other organisms can be and are transmitted through discharged patients, staff and visitors and are all over the hospital grounds — on elevators, door handles, bathroom surfaces and more.

The World Health Organization warns that crowded hospital conditions, frequent transfers of patients from one unit to another and a concentration of highly susceptible patients (e.g., newborns, intensive care patients and burn patients) further increase the probability of a hospital-acquired infection.

What can you do?

- Use the hand sanitizer provided by the hospitals.

- Wash your hands properly before, during and after visiting a hospital.

- Avoid visiting a hospital when you have an illness — your immune system is weakened during illnesses and you risk infecting others.

- If you are planning a natural birth and the cleanliness of your hospital concerns you, look into other options — a birth center or a home birth.

- Breastfeed your newborn.

Mar 09, 2012

Editor: Although the date of publication may not be current the information is still valid.

Be the first to comment on "Superbugs, Hospital-Acquired Infections (HAIs) and How They’re Spread"